AI Governance in Third-Party Risk Management: How to Make Automated Decisions Defensible

Most Third-Party Risk Management (TPRM) teams have already lived through the first round of AI promises. The sales story was ambitious, expectations were high, and early deployments were mixed. Some processes improved. Others became more complicated. Quite a few questions were parked under “we will sort this out later.”

That “later” is here. For many organizations AI now sits inside intake, scoring, routing, and monitoring. It influences which third parties move quickly, which stall, and which end up in front of senior leaders. At this point AI is part of the control environment, and it is reasonable to ask whether its decisions are defensible.

As AI becomes embedded in TPRM workflows, the priority moves from experimentation to accountable operation. Governance is the mechanism that keeps AI behavior aligned with policy, regulatory expectations, and risk appetite. This article looks at that shift and covers:

- Defining accountability for AI decisions

- How oversight, documentation, and validation keep logic from drifting

- How transparency and audit trails create trust in AI supported decisions

- What starts to erode when governance falls behind

- A concise checklist TPRM teams can use to pressure test their current state

1. Defining accountability for AI decisions

A third-party risk function applies policy, meets regulatory expectations, identifies and assesses third party risks, supports mitigation and monitoring, and gives leadership a credible picture of exposure. AI does not change those responsibilities. It changes how much work can be processed, how quickly it moves, and where people are involved.

If AI can adjust risk scores, move third parties between tiers, shorten reviews, or relax certain paths, it is already influencing risk posture. When there is no clear agreement on where automation stops and human responsibility starts, the program slides from “we follow this standard” to “we follow whatever the system is set to do.”

A basic governance discussion should settle three points:

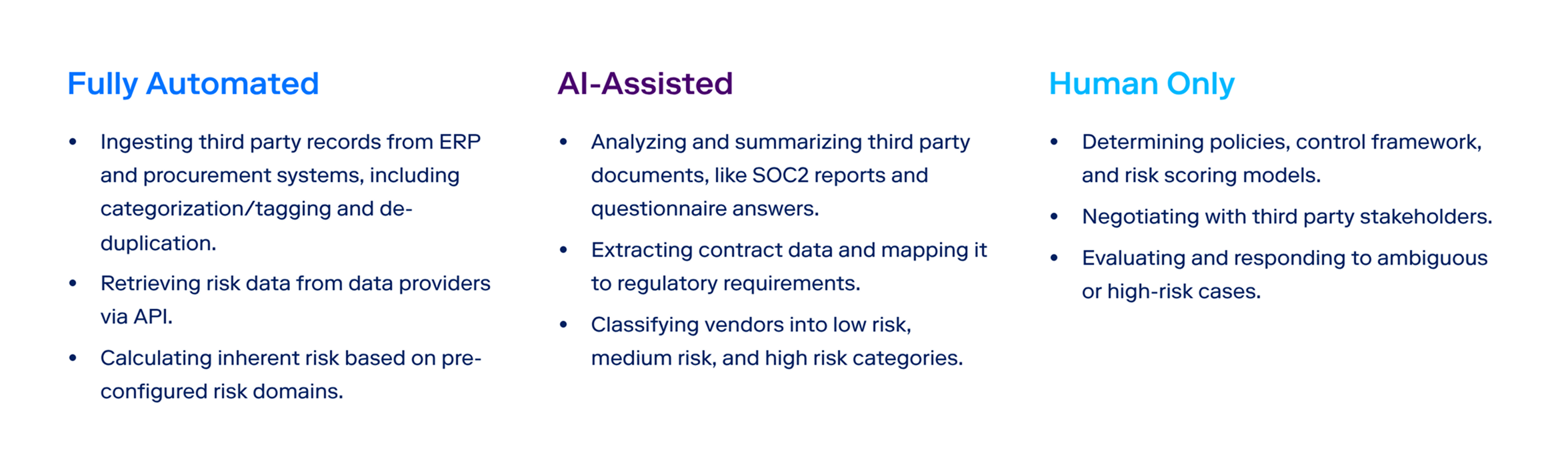

- Which decisions the system can execute without human signoff

- Where it can propose an outcome and a person must confirm

- Where automation is out of scope, regardless of technical feasibility

If you cannot point to a document that sets those boundaries, they are probably being negotiated case by case, which drives inconsistency and long-term risk.

What to look for

In leadership and committee meetings, listen for explanations that lean on “the system does that” or “I think it works this way” instead of policy, standards, or procedures. That is a signal that governance is lagging behind the technology.

2. Oversight, documentation, and validation in practice

In a third-party risk program, governance is part of the day-to-day work. It shows up in who owns the logic, how that logic is documented, and how often it is checked against real decisions and data.

Oversight

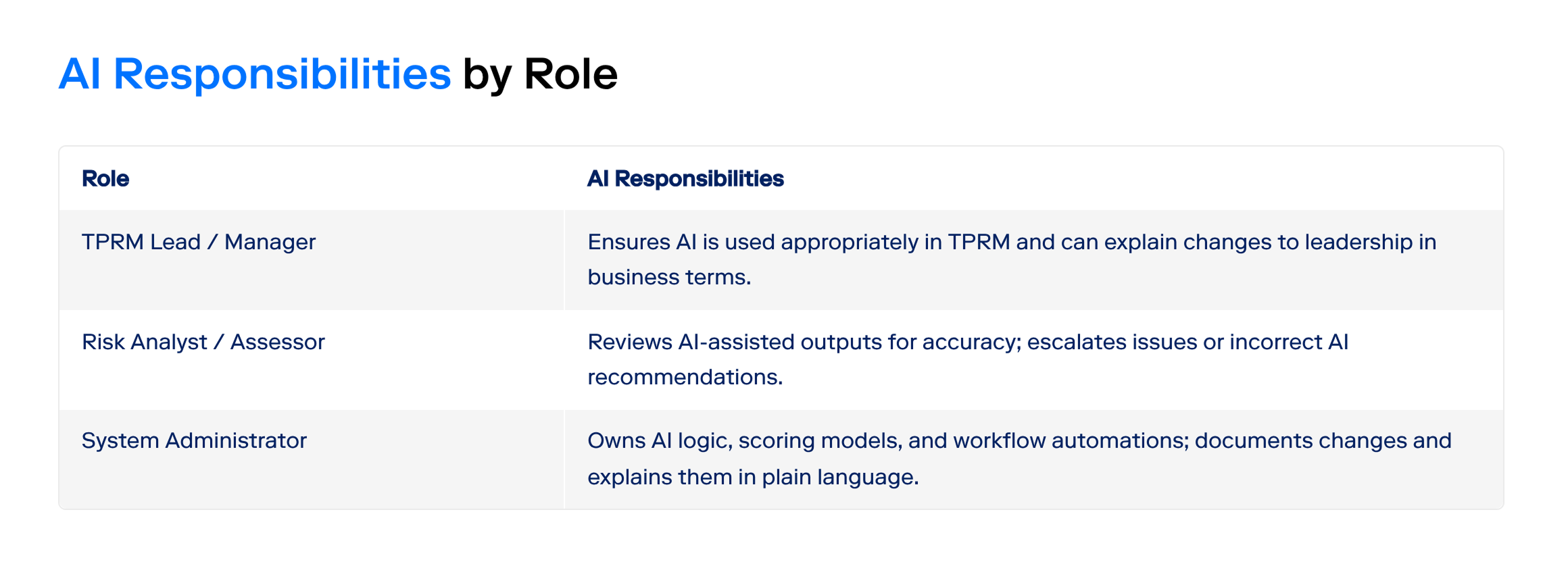

Someone must own the rules. Not “the platform” and not “operations.” A named role or small group is accountable for how risk logic, routing, and exception conditions are configured.

The owner knows which rules are active, which are being tested, and which shortcuts have been rejected. They can explain what changed, why it changed, and who approved it. Configuration choices are treated as risk decisions, not as simple convenience settings.

Without clear ownership, logic evolves through ad hoc requests and urgent tickets, and the system starts to reflect reactions instead of a deliberate risk strategy.

Documentation

If a rule only exists inside admin settings that most people never see, it behaves like hidden system logic rather than a governed control. A governed rule has a clear written reference that anyone in risk, audit, or compliance can understand without opening the tool.

A workable record should spell out:

- Which policy, standard, or control the rule supports

- Where the rule or threshold applies and to which third party groups or scenarios

- Any assumptions, limits, or conditions that shaped how the rule was designed

This does not require a long manual. A concise rule or model inventory is enough, as long as it is current and reflects how the system behaves in production.

If understanding a rule starts with “log into the platform and click around,” documentation is weak. The first step should be to pull up the record that explains why the rule exists and where it applies, then confirm that the configuration matches that description.

Validation

Logic that appears well structured in design sessions can still produce surprising or unhelpful outcomes when it runs on real third party data. Validation means reviewing AI supported decisions on a regular cadence and checking whether they align with how the organization expects to treat risk.

Questions include:

- Are the high risk third parties getting labeled as such?

- Are low risk vendors avoiding unnecessary escalation and delay?

- Are there obvious false positives or blind spots?

If the pattern does not match expectations, the rule set needs to change. The story should not be rewritten to justify the outputs.

Without validation, small misalignments accumulate. The result is a risk view that appears structured but does not reflect how the organization wants to manage exposure.

3. Transparency and audit trails as trust builders

People will not trust what they cannot see.

Transparency means anyone reviewing a decision can see what drove it. That does not require exposing math. It requires exposing the drivers. For example:

- Data classification changed

- A required control failed or slipped

- External monitoring surfaced a new signal

- The vendor profile moved into a more sensitive category

These reasons can be summarized in a sentence, but they need to be visible where people make decisions.

Audit trails extend that visibility over time. They show:

- What did the system do and when

- Where humans overrode the outcome and why

- Which version of the logic was active at that point

When these elements are available in a single view, the organization can reconstruct how and why AI influenced a vendor decision, even months or years later.

What to look for

Pick one vendor and try to rebuild its decision history using only what the platform records. If you need offline notes, personal memory, or exported spreadsheets to fill gaps, transparency and auditability are not where they need to be.

4. What starts to break when governance falls behind

Weak governance rarely fails in one moment. It shows up in small shifts. Thresholds get relaxed to clear a backlog and never reset. An exception for one strategic vendor quietly turns into the default handling for similar cases. Teams give different explanations for the same score because each person remembers a different change.

On paper, the program still has policies and standards. In day-to-day work, many outcomes are driven by configuration history, shortcuts, and inherited system logic rather than deliberate risk decisions. AI then amplifies these accumulated adjustments instead of improving consistency.

When something goes wrong, the organization will still be held accountable for the outcome. “That is how the system was set up” is not a defensible response.

A simple governance checklist for TPRM teams

Governance does not need a complex framework to be effective. But, it must be explicit and enforced. Use these prompts as a review list for your AI related controls.

Based on the information above, here is a check list for you to ensure your team is using AI responsibly.

Scope

- List the decisions that are fully automated, AI assisted, and always human only, using a chart like this one. Keep that list available to risk, compliance, and audit.

- Here is an example of a chart a TPRM team may create

Ownership

- Confirm there is a specific role or group that owns AI related logic and workflows and can describe recent changes in business terms.

Alignment

Periodically select a small sample of high-impact rules or thresholds from the TPRM platform and confirm that each one is explicitly supported by a written policy, standard, or risk appetite statement. If a rule cannot be traced back to documented guidance, either adjust the configuration or update the relevant governance document so the system is not silently creating its own risk appetite.

Examples

- An auto-approval rule for low-risk vendors should tie directly to language in the Third-Party Risk Policy that permits “streamlined due diligence” for low-risk relationships.

- A rule that automatically escalates any vendor handling customer PII in a new jurisdiction should map to a Data Protection Standard that requires enhanced review for cross-border data transfers.

- A threshold that downgrades a vendor’s risk tier based on monitoring score improvements should align with a risk appetite statement that specifies when tier changes require human approval.

Traceability

On a recurring basis, select a recent AI driven vendor decision and confirm that the platform provides a clear, end-to-end explanation of how the decision was reached. The reviewer should be able to see which inputs were used, which rules or models were triggered, and why the final classification was assigned. The goal is to ensure that decisions are explainable inside the system without exporting data or reconstructing calculations offline.

Examples:

- The AI agent flags a vendor as “High Risk.” Open the vendor record and review the explanation panel that shows which inherent risk answers drove the score increase, which rules fired, and how the system interpreted the data. Confirm that a reviewer could look at this information and reasonably understand why the High Risk

- A monitoring alert triggers an automatic escalation. Review the alert history and rule explanation to confirm the platform shows what changed, why it mattered, and how that change met the escalation criteria.

Change control

- Review a few recent logic or workflow changes and verify that each followed a defined review path, with a visible record of what changed, who approved it, and when it went live.

Validation

- Compare AI influenced outcomes with the judgments your team would expect to see and adjust rules or thresholds when gaps show up consistently.

If too many of these reviews raise questions or depend on someone’s memory, AI is already running ahead of your governance, and it is time to close that gap.

Closing thought

AI on its own is not a strategy. However, it can be an excellent tool a third-party risk program can use to carry out its strategy. Governance is what keeps that relationship clear. When AI operates within defined boundaries, backed by documentation and audit evidence, it reinforces the risk view leadership depends on. Without that structure, it can accelerate decisions that the organization may struggle to explain or defend.